China’s Muslims: A Nexus of Needles and AIDS

I've always been fascinated by how a Muslim enclave with very little outside support has managed to sustain itself and continue practising. It's not like the Chinese government is even likely to have been sympathetic.

By HOWARD W. FRENCH

KASHGAR, China, Nov. 6 — The story of Almijan, a gaunt 31-year-old former silk trader with nervous eyes, has all the markings of a public health nightmare.

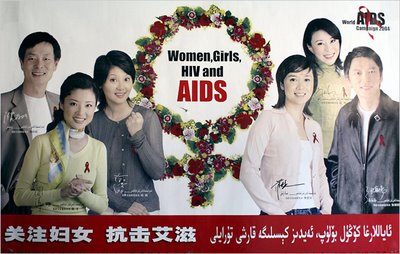

An AIDS poster in Kashgar in the Xinjiang region, which has one-tenth of China’s AIDS cases and the highest H.I.V. infection rate in the nation.

Kashgar, in a mainly Muslim area, is part of a battle against AIDS.

A longtime heroin addiction caused him to burn through $60,000 in life savings. Today, he says, all of his drug friends have AIDS and yet continue to share needles and to have sex with a range of women — with their wives, with prostitutes, or as he said, “with whoever.”

For now, Mr. Almijan, whose name like many here is a single word, seems to have escaped the nightmare. His father carted him off to a drug treatment center hundreds of miles away in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region here in China’s far west.

When he relapsed, he was arrested during a drug deal. That landed him in a new methadone clinic, opened last year in this city, where he spent three months cleaning himself up. He says he has repeatedly tested negative for H.I.V.

This day, fresh from a clinic just off of People’s Square here, watched over by a huge statue of Mao, Mr. Almijan slurred thickly after drinking the dose that keeps his cravings at bay. “If I can help other people, I’d be happy to tell you my story,” he said. He explained why he had embraced treatment: “My friends were dying, and I was very afraid.”

The way the authorities handled Mr. Almijan, including his treatment with methadone, is part of a sea change by the Chinese public health establishment, which is struggling to confront an increase in intravenous drug use and an attendant rise in AIDS cases in Xinjiang, an overwhelmingly Muslim region close to the rich poppy fields of Afghanistan and near the border with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

With a population of about 20 million and an officially estimated 60,000 infections, Xinjiang has one-tenth of China’s AIDS cases and the highest H.I.V. infection rate in the country. Chinese authorities estimate that Kashgar Prefecture, with a population of about three million, has 780 cases, but public health experts here say the real figure is probably four times that and rising fast.

Until recently, addicts were largely left to the police, who regarded them as simple criminals whose drug use was to be combated mercilessly. Resistance to treating drug addiction as a public health concern has been high, mirroring what some international health experts say was a slow response to the virus generally in China as AIDS first gained a foothold.

“Some cadres are not willing to launch a public campaign against AIDS, fearing it would affect their image and investment in their locality,” said Parhat Halik, the deputy commissioner for Kashgar Prefecture, in a speech in June. “Some are still having endless debates about whether to promote the use of condoms, methadone treatment and needle exchange programs, or standing in the way of initiatives to work with high-risk groups. That is our biggest problem in the fight against AIDS.”

But since 2005, the authorities in Xinjiang have been trying everything from needle exchanges and drug substitution programs — approaches that first became popular in the West in the 1960s — to community outreach programs, often giving briefings to imams and mullahs.

The people of Xinjiang are ethnically distinct from China’s Han majority, and have a long history of distrust of the central government.

In the narrow, winding alleys of this city, where most women wear veils and mosques can be found every hundred yards or so, Islamic clerics spoke enthusiastically about antinarcotics efforts.

“These people are killed and arrested, persecuted and punished by the police, and the price of their drugs becomes greater even than gold, and yet they continue to use them,” said Abdu Kayaum, imam at a small brick mosque here. “If I didn’t preach about these ills, I wouldn’t be a Muslim.”

At another mosque, the muezzin, or prayer caller, Abulkasim Hajim, put it slightly differently, saying: “This is not just a problem for the government, it’s a problem for our people. The people who use drugs are going to die, but before they do so, they will waste their family’s money and cause a lot of suffering.”

Mr. Hajim might well have been speaking of Mr. Almijan, whose costly 12-year habit ruined his family’s lucrative silk trading business, left him deep in debt and finally reduced him to a lowly job at a small hotel.

Now, less than a month out of detention in the treatment center, he reports most days to the clinic near Yuandong Hospital where he goes voluntarily to drink a dose of methadone under the watchful eye of a video monitor. Each treatment costs him about $1.20.

“All my money has gone up in smoke,” Mr. Almijan said, explaining that he lacks the capital to get back into the silk trade. “My friends all shared needles when I was using drugs. At least I understood how bad that was and only used my own.”

Another heroin addict, a fruit seller dressed in a tweed jacket who goes by the name Ablimit, said he started injecting heroin in 1999. “I had a bunch of friends invite me to try heroin,” he said. “They either shared a lot of needles or they overdosed. They’re all dead now.”

Mr. Ablimit, who said he had tested negative for H.I.V., has tried to break his heroin addiction many times, including a previous bout with methadone. He recently spent 45 days in a methadone treatment center after his wife caught him shooting up at home and threatened to leave him.

He said that while methadone had given him great relief from cravings for the drug, it was a not a cure. Cravings return when the methadone wears off, and weaning recovering heroin addicts from the replacement drug can be as hard as quitting heroin itself — and some say harder.

Nowadays, Mr. Ablimit works in a neighborhood recreation center, where he helps counsel other addicts and reports less and less frequently to a methadone clinic for a dose of the drug he is trying to wean himself from.

“You can take methadone as long as you want,” he continued, his wife looking on. “But I’ve got children and want to be a regular person. I want to atone for all the bad I have done.”

By HOWARD W. FRENCH

KASHGAR, China, Nov. 6 — The story of Almijan, a gaunt 31-year-old former silk trader with nervous eyes, has all the markings of a public health nightmare.

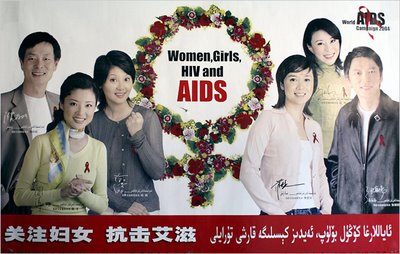

An AIDS poster in Kashgar in the Xinjiang region, which has one-tenth of China’s AIDS cases and the highest H.I.V. infection rate in the nation.

Kashgar, in a mainly Muslim area, is part of a battle against AIDS.

A longtime heroin addiction caused him to burn through $60,000 in life savings. Today, he says, all of his drug friends have AIDS and yet continue to share needles and to have sex with a range of women — with their wives, with prostitutes, or as he said, “with whoever.”

For now, Mr. Almijan, whose name like many here is a single word, seems to have escaped the nightmare. His father carted him off to a drug treatment center hundreds of miles away in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region here in China’s far west.

When he relapsed, he was arrested during a drug deal. That landed him in a new methadone clinic, opened last year in this city, where he spent three months cleaning himself up. He says he has repeatedly tested negative for H.I.V.

This day, fresh from a clinic just off of People’s Square here, watched over by a huge statue of Mao, Mr. Almijan slurred thickly after drinking the dose that keeps his cravings at bay. “If I can help other people, I’d be happy to tell you my story,” he said. He explained why he had embraced treatment: “My friends were dying, and I was very afraid.”

The way the authorities handled Mr. Almijan, including his treatment with methadone, is part of a sea change by the Chinese public health establishment, which is struggling to confront an increase in intravenous drug use and an attendant rise in AIDS cases in Xinjiang, an overwhelmingly Muslim region close to the rich poppy fields of Afghanistan and near the border with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

With a population of about 20 million and an officially estimated 60,000 infections, Xinjiang has one-tenth of China’s AIDS cases and the highest H.I.V. infection rate in the country. Chinese authorities estimate that Kashgar Prefecture, with a population of about three million, has 780 cases, but public health experts here say the real figure is probably four times that and rising fast.

Until recently, addicts were largely left to the police, who regarded them as simple criminals whose drug use was to be combated mercilessly. Resistance to treating drug addiction as a public health concern has been high, mirroring what some international health experts say was a slow response to the virus generally in China as AIDS first gained a foothold.

“Some cadres are not willing to launch a public campaign against AIDS, fearing it would affect their image and investment in their locality,” said Parhat Halik, the deputy commissioner for Kashgar Prefecture, in a speech in June. “Some are still having endless debates about whether to promote the use of condoms, methadone treatment and needle exchange programs, or standing in the way of initiatives to work with high-risk groups. That is our biggest problem in the fight against AIDS.”

But since 2005, the authorities in Xinjiang have been trying everything from needle exchanges and drug substitution programs — approaches that first became popular in the West in the 1960s — to community outreach programs, often giving briefings to imams and mullahs.

The people of Xinjiang are ethnically distinct from China’s Han majority, and have a long history of distrust of the central government.

In the narrow, winding alleys of this city, where most women wear veils and mosques can be found every hundred yards or so, Islamic clerics spoke enthusiastically about antinarcotics efforts.

“These people are killed and arrested, persecuted and punished by the police, and the price of their drugs becomes greater even than gold, and yet they continue to use them,” said Abdu Kayaum, imam at a small brick mosque here. “If I didn’t preach about these ills, I wouldn’t be a Muslim.”

At another mosque, the muezzin, or prayer caller, Abulkasim Hajim, put it slightly differently, saying: “This is not just a problem for the government, it’s a problem for our people. The people who use drugs are going to die, but before they do so, they will waste their family’s money and cause a lot of suffering.”

Mr. Hajim might well have been speaking of Mr. Almijan, whose costly 12-year habit ruined his family’s lucrative silk trading business, left him deep in debt and finally reduced him to a lowly job at a small hotel.

Now, less than a month out of detention in the treatment center, he reports most days to the clinic near Yuandong Hospital where he goes voluntarily to drink a dose of methadone under the watchful eye of a video monitor. Each treatment costs him about $1.20.

“All my money has gone up in smoke,” Mr. Almijan said, explaining that he lacks the capital to get back into the silk trade. “My friends all shared needles when I was using drugs. At least I understood how bad that was and only used my own.”

Another heroin addict, a fruit seller dressed in a tweed jacket who goes by the name Ablimit, said he started injecting heroin in 1999. “I had a bunch of friends invite me to try heroin,” he said. “They either shared a lot of needles or they overdosed. They’re all dead now.”

Mr. Ablimit, who said he had tested negative for H.I.V., has tried to break his heroin addiction many times, including a previous bout with methadone. He recently spent 45 days in a methadone treatment center after his wife caught him shooting up at home and threatened to leave him.

He said that while methadone had given him great relief from cravings for the drug, it was a not a cure. Cravings return when the methadone wears off, and weaning recovering heroin addicts from the replacement drug can be as hard as quitting heroin itself — and some say harder.

Nowadays, Mr. Ablimit works in a neighborhood recreation center, where he helps counsel other addicts and reports less and less frequently to a methadone clinic for a dose of the drug he is trying to wean himself from.

“You can take methadone as long as you want,” he continued, his wife looking on. “But I’ve got children and want to be a regular person. I want to atone for all the bad I have done.”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home