Israel's debacle, courtesy of Bush

With U.S. support, Israeli unilateralism was unfurled. The nation has never been so endangered, or its moral authority so tarnished.

By Sidney Blumenthal

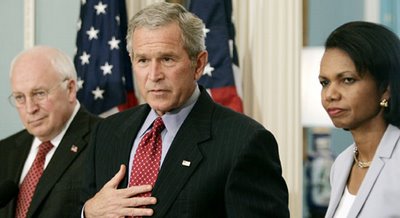

Aug. 17, 2006 | On Monday, the day the cease-fire was imposed on Israel's war in Lebanon against Hezbollah, and just days after the London terrorists were arrested, President Bush strode to the podium at the State Department to describe global conflict in neater and tidier terms than any convoluted conspiracy theory. Almost in one breath he explained that events "from Baghdad to Beirut," and Afghanistan, and London, are linked in "a broader struggle between freedom and terror"; that far-flung terrorism is "no coincidence," caused by "a lack of freedom" -- "We saw the consequences on September the 11th, 2001" -- and that all these emanations are being combated by his administration's "forward strategy of freedom in the broader Middle East," and that "that strategy has helped bring hope to millions." If there was any doubt about "coincidence," he concluded a sequence stringing together Lebanon, Iraq and Iran by defiantly pledging, "The message of this administration is clear: America will stay on the offense against al-Qaida." Thus Bush's unified field theory of fear, if it is a theory.

Then, once again, Bush declared victory. Hezbollah, he asserted, had gained nothing from the war, but had "suffered a defeat."

At the moment that Bush was speaking an Israeli poll was released that revealed the disintegration of public opinion there about the war aims and Israeli leadership. Fifty-two percent believed that the Israeli army was unsuccessful, and 58 percent believed Israel had achieved none of its objectives. The disapproval ratings of Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and Defense Minister Amir Peretz skyrocketed to 62 percent and 65 percent, respectively.

The war has left Israel's invincible image shattered and moral authority tarnished, while leaving Hezbollah standing on the battlefield, its reputation burnished in the Arab street "from Baghdad to Beirut." Virtually the entire Israeli political structure has emerged from the ordeal discredited. When the war against Hezbollah ended, the war of political and military leader against each other began.

"You cannot lead an entire nation to war promising victory, produce humiliating defeat and remain in power," wrote Ari Shavit, a columnist for Haaretz, which published his call for the replacement of Olmert on its front page. As the political leaders accused one another of blunders, and beat their breasts in a desperate effort to survive (Olmert confessed "deficiencies"), the military commanders attacked and counterattacked. Gen. Udi Adam, head of the Israel Defense Forces Northern Command, who had been ousted as the offensive turned sour, gave a newspaper interview blaming the government for confusion and errors. Dan Halutz, the IDF chief of staff, issued an order forbidding all army personnel from giving press interviews, just as the newspapers were filled with the shocking exposé that Halutz had sold a stock portfolio within hours of learning of the Hezbollah kidnapping of two Israeli soldiers but before the Israeli government announced a response. The Knesset began an investigation. "We simply blew it," ran the headline on another column in Haaretz.

Israel's strategic debacle was a curiously warped and accelerated version of the U.S. misadventure in Iraq. It used mistaken means in pursuit of misconceived goals, producing misbegotten failure. Rather than seek the disarmament of Hezbollah, Israel sought to eliminate it permanently. If the aim had been to disarm it, in line with United Nations Resolution 1559, Israel might have initiated a diplomatic round, drawing in Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Egypt, to help with the Lebanese government. But, encouraged by the Bush administration, Israel treated Lebanese sovereignty as a fiction. With U.S. support, Israeli unilateralism was unfurled. The possible consequences of anything less than stunning and complete triumph in a place where Israel had long experienced disaster were dismissed.

After having withdrawn in 2000 from its occupation of Lebanon, achieving few of the aims declared in the 1982 invasion, the Israeli government launched an air campaign that would supposedly extirpate Hezbollah. The wishful thinking behind the air campaign was similar to that of the Bush administration in its invasion of Iraq. Upon the liberators' entry into Baghdad, Vice President Cheney explained beforehand, the population would greet them with flowers. In Lebanon, the idea was that the more destruction wreaked by Israel, the more the population would blame Hezbollah. Of course, as common sense and every previous historical example should have dictated, the opposite occurred. When the air campaign obviously failed, the army was thrown into the breach, sent to relive Israel's 1982 agony. Cautions about repeating the past were ignored, and the past was repeated.

Israel's national security has never been so damaged and endangered. And none of it would have been possible without the Bush administration's incitement and backing at every calamitous turn. The further erosion of U.S. credibility has also been severe.

As Bush made clear in his Monday press conference, the administration conceived of the Israeli offensive in Lebanon as a third front in his global war on terror, after Iraq and Afghanistan. Opening this new front, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said, was part of the "birth pangs" of "a new Middle East." With the third front, Bush redoubled his bets on his entire policy. Some in the administration hoped that it might open fourth and fifth fronts in Syria and Iran.

The administration used diplomacy to forestall diplomacy. It became Bush's instrument for giving the Israeli offensive free rein. As administration officials encouraged the Israelis in their strategy, they reinforced the Israeli government's illusionary belief that air power alone could rapidly bring about a wondrous victory.

After deliberately dallying, Rice belatedly made her way to the region, where she conducted feckless discussions in order to give the Israelis more time. She had already made her separate peace with Cheney and his covey of neoconservatives, and she was inclined to believe whatever the Israelis said. She was heedless of the analysis of State Department experts and the urgent warnings of her erstwhile mentor, Brent Scowcroft, the elder Bush's national security advisor.

Instead of recognizing that the Israelis were encountering difficulties, Rice served as the stalwart enabler of the collapsing strategy. But the limitations of her utility were exposed when the Israelis neglected to inform her of the bombing of the town of Qana, where at least 26 civilians, including 16 children, were killed. The fig leaf of her influence was removed.

No administration official has suffered more collateral damage from the Lebanon war than Rice. Her flights to and fro have exposed her as vacillating and reckless, fretful and compliant, opportunistic but myopic, and in every guise ineffective. She wound up as the cheerleader on the rubble.

It can be said with a high degree of certainty, not simply tragic precedent, that the Bush administration engaged in this latest fiasco by ignoring the caveats and worst-case scenarios that must have been produced by the intelligence community. It is inconceivable that there was no intelligence assessment of Hezbollah's military, social and political capabilities, along with a range of potential outcomes. Unquestionably, such documents exist. One of them might well have taken the form of a Presidential Daily Briefing, which would have been presented to Bush by National Intelligence Director John Negroponte. It is also inevitable to conclude that having been briefed, Bush heard only what he wanted to hear.

Afterward, as the Israelis tore at one another, Bush proclaimed victory, following his Iraq P.R. formula. While his phrases might be a tonic to his political base, the rest of the world, especially now the Israelis, receive it as the empty rhetoric it is. The more Bush declares success when there is failure, the more U.S. credibility is tattered.

Perhaps the most important and unanswerable question is whether Bush believes his own propaganda. Whether he believes what he says is beside the point, because the only thing that matters is that he acts on it. The propaganda may be false and distorted. It may be historically and analytically meaningless, like Bush's recent adoption of the neoconservative ideological code words "Islamic fascism," lacking in any significant empirical value. But such pejorative phrases are helpful in stymieing public debate by evoking connotations of Hitler and Mussolini, who never dreamed of restoring a mythical caliphate. Bush's propaganda is his policy. And with every failure, it seems a new front is opened.

On the day Bush declared the defeat of Hezbollah in Lebanon, he had an unusual lunch at the Pentagon with four experts on Iraq, only one of whom was a neoconservative. According to their accounts, Bush was perturbed and baffled by the demonstrations of Iraqi Shiites in support of Hezbollah. "I do think he was frustrated about why 10,000 Shiites would go into the streets and demonstrate against the United States," one participant told the New York Times. Yet another expert, Carole O'Leary, a professor at American University and a State Department consultant, observed that Bush stressed that "the Shia-led government needs to clearly and publicly express the same appreciation for US efforts and sacrifices as they do in private."

Bush's demand for expressions of gratitude from the Iraqis is not a new one. In his memoir, L. Paul Bremer III, head of the ill-fated Coalition Provisional Authority, records that above all other issues Bush stressed the need for an Iraqi government to declare its thanks. "It's important to have someone who's willing to stand up and thank the American people for their sacrifice in liberating Iraq," Bush told Bremer three times in one meeting. Puzzled by Shiite solidarity with Hezbollah, Bush's demand for gratitude remains unchanged.

This week Bush broke from his usual long summer vacation at Crawford, Texas for a press conference and meetings in Washington. The week before, while the Lebanon war was still raging, Bush invited Reuters correspondent Steve Holland to join him on an hour and a half bicycle ride in 100-degree heat. (Bush holds contests for his staff at Crawford to belong to his "100-Degree Club." When the temperature hits 100 degrees, they run three miles while the president rides his bike alongside them, urging them to run faster. "You can do it!" At the end, they receive T-shirts and pose for pictures with Bush.) "Bush does not ride quietly, constantly shouting out in his Texas twang the names of trees and geographic features and yelling at himself to pedal faster," Holland wrote. As Bush rode up a hill, leading an entourage of sweating Secret Service agents and the reporter, he shouted to no one in particular: "Air assault!"

From an article in salon.com, by Sidney Blumenthal

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home