Baladi wear

Two local artists tell the story of 20th century Egypt through its consumer products

By Matt Hall

Artists over the centuries, from Michelangelo to Donald Judd, have relied on professional draftsmen to realize their visions. With her latest works, renowned Cairo-based artist Lara Baladi has gone one step further: She didn’t even design them.

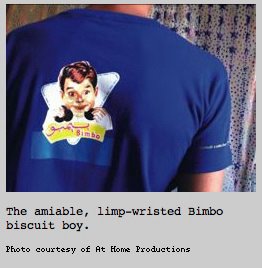

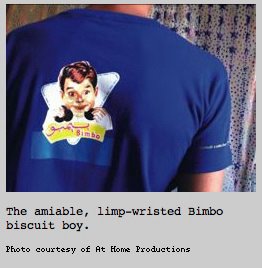

The latest offering from Baladi and partner Ayman Ezzat is a line of t-shirts featuring logos and designs from some of Egypt’s most recognizable brands. Colorful tees are emblazoned with the red and yellow Al Aroussa box, the golden fez of Tarboush laundry bleach, the limp-wristed boy of Bimbo biscuits and other inimitable designs.

But the art is in the assemblage, the narrative that is established through curating Egypt’s visual heritage. “These everyday objects,” explains Baladi, “in a way define who we are.” As Egypt—like the rest of the world—experienced hyper-commercialization in the last half century, its historical remembrances have become inextricably linked with consumption. Products and brands have become signposts of our times; Nike shoes and iPods have come to define decades as much as political events. “My family moved to Egypt from Lebanon when I was quite young,” says Baladi, “and one of the things I think of when remembering growing up in Cairo is Bimbo chocolates—reaching my hand through the gate after school to buy these biscuits from the Bimbo man.”

These products serve not simply as mnemonic devices for the nostalgic, but also as telling artifacts of their times. “If you look at the original label on Tarboush bleach,” notes Baladi, “it’s printed in four different languages—Farsi, French, Greek and Armenian—that’s Egypt in the 1940s.”

It is no mistake, then, that Baladi and Ezzat’s collection has been named Tarikh Baladi (History of My Country). “The first three shirts begin to trace our [pre-revolutionary] history,” explains Baladi, “from the Ottoman rolling papers to the tarbush of Tarboush bleach to Al Basha’s little basha figure.”

At the center of the collection is Al Masryeen shampoo, whose name (The Egyptian People) and logo (a fist rising from the national flag) are evocative of the revolution, the pivotal event of modern Egyptian history.

The collection’s title, Tarikh Baladi, can of course be read as both “history of my country” and, because of the pun with the artist’s name, “my history.” If Al Masryeen shampoo is central to the national narrative, Al Aroussa tea—the most current of the brands—is central to Baladi’s personal history.

Not only has the artist drunk the tea faithfully for the last 15 years, she has met with the company’s owner and the product designer to discuss the merits of this particular powder tea. To hear Baladi expound on the constellation of symbols embedded in the box’s design is like listening to a numerologist going through the phone book.

“One of the things I love about the Aroussa design is its shameless copying of Marlboro cigarettes. Some people don’t see it at first, but once you point it out they can’t miss it... absolutely shameless—I love it!” In fact, Al Aroussa was actually sued (unsuccessfully) by the Marlboro Corporation over the striking resemblance of its design.

The Aroussa t-shirt is the ninth and final in the series. “With the Savo t-shirt we begin to see the onset of commercialism and outside influence—its gaudy 1960s design,” explains Baladi. “With Aroussa we are where we are today. We have incorporated this globalization—by copying Marlboro, the most famous brand in the world—and changed it and made it our own.”

Baladi, born in 1969, has received much recognition for her imaginative and arresting photography and mixed-media works. The idea for the t-shirts germinated through collaboration with Ezzat, a product of the Chicago House music scene and the founder of At Home productions, which organizes dance parties. A CD of music by At Home DJs is included with each T-shirt.

It is perhaps ironic that Baladi and Ezzat chose to tell Egyptian history via a medium as democratic as t-shirts. “I wanted to get away from the art world,” says Baladi, “to reach people some other way than through galleries.”

William sent this.

By Matt Hall

Artists over the centuries, from Michelangelo to Donald Judd, have relied on professional draftsmen to realize their visions. With her latest works, renowned Cairo-based artist Lara Baladi has gone one step further: She didn’t even design them.

The latest offering from Baladi and partner Ayman Ezzat is a line of t-shirts featuring logos and designs from some of Egypt’s most recognizable brands. Colorful tees are emblazoned with the red and yellow Al Aroussa box, the golden fez of Tarboush laundry bleach, the limp-wristed boy of Bimbo biscuits and other inimitable designs.

But the art is in the assemblage, the narrative that is established through curating Egypt’s visual heritage. “These everyday objects,” explains Baladi, “in a way define who we are.” As Egypt—like the rest of the world—experienced hyper-commercialization in the last half century, its historical remembrances have become inextricably linked with consumption. Products and brands have become signposts of our times; Nike shoes and iPods have come to define decades as much as political events. “My family moved to Egypt from Lebanon when I was quite young,” says Baladi, “and one of the things I think of when remembering growing up in Cairo is Bimbo chocolates—reaching my hand through the gate after school to buy these biscuits from the Bimbo man.”

These products serve not simply as mnemonic devices for the nostalgic, but also as telling artifacts of their times. “If you look at the original label on Tarboush bleach,” notes Baladi, “it’s printed in four different languages—Farsi, French, Greek and Armenian—that’s Egypt in the 1940s.”

It is no mistake, then, that Baladi and Ezzat’s collection has been named Tarikh Baladi (History of My Country). “The first three shirts begin to trace our [pre-revolutionary] history,” explains Baladi, “from the Ottoman rolling papers to the tarbush of Tarboush bleach to Al Basha’s little basha figure.”

At the center of the collection is Al Masryeen shampoo, whose name (The Egyptian People) and logo (a fist rising from the national flag) are evocative of the revolution, the pivotal event of modern Egyptian history.

The collection’s title, Tarikh Baladi, can of course be read as both “history of my country” and, because of the pun with the artist’s name, “my history.” If Al Masryeen shampoo is central to the national narrative, Al Aroussa tea—the most current of the brands—is central to Baladi’s personal history.

Not only has the artist drunk the tea faithfully for the last 15 years, she has met with the company’s owner and the product designer to discuss the merits of this particular powder tea. To hear Baladi expound on the constellation of symbols embedded in the box’s design is like listening to a numerologist going through the phone book.

“One of the things I love about the Aroussa design is its shameless copying of Marlboro cigarettes. Some people don’t see it at first, but once you point it out they can’t miss it... absolutely shameless—I love it!” In fact, Al Aroussa was actually sued (unsuccessfully) by the Marlboro Corporation over the striking resemblance of its design.

The Aroussa t-shirt is the ninth and final in the series. “With the Savo t-shirt we begin to see the onset of commercialism and outside influence—its gaudy 1960s design,” explains Baladi. “With Aroussa we are where we are today. We have incorporated this globalization—by copying Marlboro, the most famous brand in the world—and changed it and made it our own.”

Baladi, born in 1969, has received much recognition for her imaginative and arresting photography and mixed-media works. The idea for the t-shirts germinated through collaboration with Ezzat, a product of the Chicago House music scene and the founder of At Home productions, which organizes dance parties. A CD of music by At Home DJs is included with each T-shirt.

It is perhaps ironic that Baladi and Ezzat chose to tell Egyptian history via a medium as democratic as t-shirts. “I wanted to get away from the art world,” says Baladi, “to reach people some other way than through galleries.”

William sent this.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home