Many Mothers

Thanks to Sherien for helping me find this.

My grandmother was ashamed enough to conceal the lump in her breast until about eighteen months after she first became aware of it. It was only after my dad had commented that she always looked worried these days, that she gently and reluctantly hinted that all was not well.

"How long has this been there?" asked my dad, wearily. He was caught between concern for his aging mother and exasperation at her temerity.

"A while" she conceded. "A year".

"Why didn't you say anything before?"

"Your father has a lot on his mind. I didn't want to worry him. So do you what with your son going to college...and your sisters, Nadia and Nabila are both having problems with their husbands..."

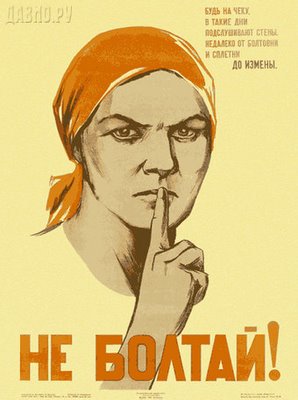

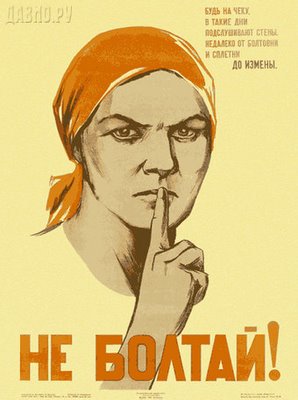

"Ya Mama bass...right time...when is it ever a right time?" snapped my dad, perhaps more severely than he intended to. My grandmother was looking away with a sort of detached sense of martyrdom, as if satisfied with what she perceived to be her ability to spare her family the burden of her sickness. This was a classic feature of older Egyptian women: a determination to be seen, not heard, a desire to provide solution and an almost manic obsession with maintaining peace and tranquility within her family, at all costs. My grandfather, as far as I could tell, had always encouraged this. His famous saying to her was 'If you can't be part of the solution, then go make dinner'.

My dad understood all this and his frustration was of someone who knew that his mother's irrational concealment of her cancer was part of a bigger cancer in our society. The mother was supposed to bear, to nurture, to comfort but never complain. And if she did, well then she was more trouble than she was worth and it was time to find wives number two through four. With that kind of threat hanging over her head, my grandmother would have concealed ten lumps for ten years. It reaffirmed her success as a wife who never complained.

She died two years later of that same cancer. At the funeral, I remember thinking that death was a good way to start over again for all the rest of us. Maybe with less women as misguided as my grandmother, people like my mother, my girlfriend and my imaginary sister would stand a chance.

When my dad was seven, he got sick with something so serious that he was in bed for seven months. When I was 22, I managed to catch Typhoid and was in bed for four months. My dad's illness was pretty serious and yet no one could remember what it was because, I suspect, nobody knew what it was. I'm sure a doctor was called but I also seem to recall a story my dad told me where he mentioned that the town barber was also responsible for curing all ailments in the village, from warts to sexual dysfunction to cancer. So if they called the barber, I'm sure my dad spent the seven months in bed with a very trendy cut but I doubt he got a lot of information about why he was in bed.

After six months of illness, my grandmother decided drastic measures were needed. She arranged for a red hot poker to be used to brand my dad's head, while three of his sisters held him down. My dad related this story with little emotion and didn't give too many details but I could tell he was making the point that I was lucky to be living in enlightened times.

He still has the mark to this day, hidden beneath a thick head of hair. As far as I can tell, he never bore my grandmother any malice about it, though I have to say he has precious little proof it didn't work. I mean, a month later, he was on his feet.

When I got typhoid, I dreamt that my dad was considering using the hot poker method on me. As a result, I kept my swiss army knife under my pillow for the duration of my illness.

I never got along with my mother and from an early age, I thought I had her figured out. Despite this arrogance, my mother still managed to shock me twice during her life. And she always did it by revealing how a number of things I absolutely hated about our society had somehow gotten to her first and were, in part, responsible for certain aspects of her nature which I considered hateful.

We were watching a show on TV about female circumcision. I turned to my mother and asked her 'How can anyone do this?', all the time watching her closely, baiting her into giving me a retort consistent with her traditionalist views, the ones that I thrived on rejecting. I imagined she would say something as clueless as 'Well, do you want our women to become whores?' and I thought I was certain that if my imaginary sister were real, she would have circumcised her too.

Her answer caught me off guard but what really surprised me was the tenderness and desperation of her delivery.

"Well, I was circumcised when I was six". I looked at her, shocked and numb to the world. Her eyes were weary and filled with longing and for the first time, in years, I connected with a humanity I thought my mother had never possessed. I thought I hated her for being obtuse and for bringing gloom to my growing heart. I realised I hated myself for never being able to help her beyond the confines of what she knew.

The second time she shocked me, she told me that when she was a little girl, she had gotten a part to sing and dance on a varieties show in the late 1950s. She was very excited and ran home to tell her mother. Times being what they were, my grandmother thrashed her to within an inch of her life. When my grandfather came home and was told about the events of the day, he thrashed her to within...an even closer distance than an inch of her life. Her musical aspirations probably died that day.

I don't know if I was shocked by how brutal my grandparents were (they of the easy smiles, the constant candy and the never-say-no-to-Mo approach), the fact that my mother ever had aspirations, never mind musical ones...or the fact she had ever been a little girl. The problem with the iconic figures in your life, the ones who end up defining who you are, is that you never think they're as human as you are.

I always wish I had a sister but I was equally glad I never had one. My stated reason for being glad I didn't have one was noble: a girl would have found it hard to endure life under the kind of regime my parents installed. Parochial, chauvinist and and repressive, she probably would have ended up running away or perhaps killing herself. But that's not the whole truth about why I was glad I didn't have a sister.

Having a sister would have forced me into making a decision about how liberal I would have been with her. It was alright to talk about being liberal, to advocate the right of women to enjoy all that a man could enjoy and to encourage women to explore their own individuality and sexuality. But when it was your own sister, how true to your words would you be?

I know the answer to that question with 99% certainty. I would have been true to my word, no doubt in my mind. So that isn't the core of my fear. My fear arises from a certain knowledge that if....when I support her rights to explore her life, openly and without shame, I would be ostracized from my family, even more than I am now. I would be alone with her, cut off from society and shunned by all those who subscribed to the view that women carried the badge of honour and shame.

Just by believing the things I believe, I am shunned by many people. But this isolation is, to a certain extent, negotiated by me, on many of my own terms. Were I to have a sister, I would be abandoned with no hope of reprieve.

I would have been true. I know that. But my fear of that is true as well.

It was shocking to me how, after two years of dating, I began to realise that my girlfriend was very similar to my mother. Both were needy, both were unstable and both could not bear my stare to go anywhere else, even for a few short minutes. They were tortured souls who wanted more than they could give. Their hearts were pure which made me hate them even more, because I couldn't blame their actions on a black heart.

One time, I was sitting in a car with my girlfriend and she had been quiet for some time. For a few weeks now, she'd been depressed at the slow drudgery of daily life. She also didn't work, so there was nothing else to distract her from the length of the day. She would cry for hours and be silent for hours, smoke continuously and drift into her thoughts in the middle of a conversation. I had failed with all my attempts to revive her. At the same time, I resented my role as her sole reviver. Why should I help her when she wasn't helping herself.

In situations like this, I revert to the ridiculous. She turned to me, in the car, and asked me softly:

"Can we stop by the bakery so I can get some coffee?"

"Bibbly, grill savan tack gwerro-derro alazondo" I said without missing a beat. Gibberish, intended to make her laugh. Instead, she looked at me for a second, her eyes widened and the she burst into tears.

Later she would tell me she thought she had lost the ability to understand language and she believed she had gone insane. At the time, I put my arms around her and told her it was okay, I was here and that nothing bad would happen to her, as long as I was here. Later, I would revel in the impact I had had on her. I had failed to breakthrough her depression before, with the usual armoury of compassion, concern, affection and attention. As it turns out, all I needed was to scare the living shit out of her. It worked too, because her outpour of emotion relieved a lot of tension for her and enabled her to find her bearings. The next day, he depression had lifted and she went back to being her.

I always resented my role as her reviver. I wondered when would it be my turn to be revived.

My grandmother was ashamed enough to conceal the lump in her breast until about eighteen months after she first became aware of it. It was only after my dad had commented that she always looked worried these days, that she gently and reluctantly hinted that all was not well.

"How long has this been there?" asked my dad, wearily. He was caught between concern for his aging mother and exasperation at her temerity.

"A while" she conceded. "A year".

"Why didn't you say anything before?"

"Your father has a lot on his mind. I didn't want to worry him. So do you what with your son going to college...and your sisters, Nadia and Nabila are both having problems with their husbands..."

"Ya Mama bass...right time...when is it ever a right time?" snapped my dad, perhaps more severely than he intended to. My grandmother was looking away with a sort of detached sense of martyrdom, as if satisfied with what she perceived to be her ability to spare her family the burden of her sickness. This was a classic feature of older Egyptian women: a determination to be seen, not heard, a desire to provide solution and an almost manic obsession with maintaining peace and tranquility within her family, at all costs. My grandfather, as far as I could tell, had always encouraged this. His famous saying to her was 'If you can't be part of the solution, then go make dinner'.

My dad understood all this and his frustration was of someone who knew that his mother's irrational concealment of her cancer was part of a bigger cancer in our society. The mother was supposed to bear, to nurture, to comfort but never complain. And if she did, well then she was more trouble than she was worth and it was time to find wives number two through four. With that kind of threat hanging over her head, my grandmother would have concealed ten lumps for ten years. It reaffirmed her success as a wife who never complained.

She died two years later of that same cancer. At the funeral, I remember thinking that death was a good way to start over again for all the rest of us. Maybe with less women as misguided as my grandmother, people like my mother, my girlfriend and my imaginary sister would stand a chance.

When my dad was seven, he got sick with something so serious that he was in bed for seven months. When I was 22, I managed to catch Typhoid and was in bed for four months. My dad's illness was pretty serious and yet no one could remember what it was because, I suspect, nobody knew what it was. I'm sure a doctor was called but I also seem to recall a story my dad told me where he mentioned that the town barber was also responsible for curing all ailments in the village, from warts to sexual dysfunction to cancer. So if they called the barber, I'm sure my dad spent the seven months in bed with a very trendy cut but I doubt he got a lot of information about why he was in bed.

After six months of illness, my grandmother decided drastic measures were needed. She arranged for a red hot poker to be used to brand my dad's head, while three of his sisters held him down. My dad related this story with little emotion and didn't give too many details but I could tell he was making the point that I was lucky to be living in enlightened times.

He still has the mark to this day, hidden beneath a thick head of hair. As far as I can tell, he never bore my grandmother any malice about it, though I have to say he has precious little proof it didn't work. I mean, a month later, he was on his feet.

When I got typhoid, I dreamt that my dad was considering using the hot poker method on me. As a result, I kept my swiss army knife under my pillow for the duration of my illness.

I never got along with my mother and from an early age, I thought I had her figured out. Despite this arrogance, my mother still managed to shock me twice during her life. And she always did it by revealing how a number of things I absolutely hated about our society had somehow gotten to her first and were, in part, responsible for certain aspects of her nature which I considered hateful.

We were watching a show on TV about female circumcision. I turned to my mother and asked her 'How can anyone do this?', all the time watching her closely, baiting her into giving me a retort consistent with her traditionalist views, the ones that I thrived on rejecting. I imagined she would say something as clueless as 'Well, do you want our women to become whores?' and I thought I was certain that if my imaginary sister were real, she would have circumcised her too.

Her answer caught me off guard but what really surprised me was the tenderness and desperation of her delivery.

"Well, I was circumcised when I was six". I looked at her, shocked and numb to the world. Her eyes were weary and filled with longing and for the first time, in years, I connected with a humanity I thought my mother had never possessed. I thought I hated her for being obtuse and for bringing gloom to my growing heart. I realised I hated myself for never being able to help her beyond the confines of what she knew.

The second time she shocked me, she told me that when she was a little girl, she had gotten a part to sing and dance on a varieties show in the late 1950s. She was very excited and ran home to tell her mother. Times being what they were, my grandmother thrashed her to within an inch of her life. When my grandfather came home and was told about the events of the day, he thrashed her to within...an even closer distance than an inch of her life. Her musical aspirations probably died that day.

I don't know if I was shocked by how brutal my grandparents were (they of the easy smiles, the constant candy and the never-say-no-to-Mo approach), the fact that my mother ever had aspirations, never mind musical ones...or the fact she had ever been a little girl. The problem with the iconic figures in your life, the ones who end up defining who you are, is that you never think they're as human as you are.

I always wish I had a sister but I was equally glad I never had one. My stated reason for being glad I didn't have one was noble: a girl would have found it hard to endure life under the kind of regime my parents installed. Parochial, chauvinist and and repressive, she probably would have ended up running away or perhaps killing herself. But that's not the whole truth about why I was glad I didn't have a sister.

Having a sister would have forced me into making a decision about how liberal I would have been with her. It was alright to talk about being liberal, to advocate the right of women to enjoy all that a man could enjoy and to encourage women to explore their own individuality and sexuality. But when it was your own sister, how true to your words would you be?

I know the answer to that question with 99% certainty. I would have been true to my word, no doubt in my mind. So that isn't the core of my fear. My fear arises from a certain knowledge that if....when I support her rights to explore her life, openly and without shame, I would be ostracized from my family, even more than I am now. I would be alone with her, cut off from society and shunned by all those who subscribed to the view that women carried the badge of honour and shame.

Just by believing the things I believe, I am shunned by many people. But this isolation is, to a certain extent, negotiated by me, on many of my own terms. Were I to have a sister, I would be abandoned with no hope of reprieve.

I would have been true. I know that. But my fear of that is true as well.

It was shocking to me how, after two years of dating, I began to realise that my girlfriend was very similar to my mother. Both were needy, both were unstable and both could not bear my stare to go anywhere else, even for a few short minutes. They were tortured souls who wanted more than they could give. Their hearts were pure which made me hate them even more, because I couldn't blame their actions on a black heart.

One time, I was sitting in a car with my girlfriend and she had been quiet for some time. For a few weeks now, she'd been depressed at the slow drudgery of daily life. She also didn't work, so there was nothing else to distract her from the length of the day. She would cry for hours and be silent for hours, smoke continuously and drift into her thoughts in the middle of a conversation. I had failed with all my attempts to revive her. At the same time, I resented my role as her sole reviver. Why should I help her when she wasn't helping herself.

In situations like this, I revert to the ridiculous. She turned to me, in the car, and asked me softly:

"Can we stop by the bakery so I can get some coffee?"

"Bibbly, grill savan tack gwerro-derro alazondo" I said without missing a beat. Gibberish, intended to make her laugh. Instead, she looked at me for a second, her eyes widened and the she burst into tears.

Later she would tell me she thought she had lost the ability to understand language and she believed she had gone insane. At the time, I put my arms around her and told her it was okay, I was here and that nothing bad would happen to her, as long as I was here. Later, I would revel in the impact I had had on her. I had failed to breakthrough her depression before, with the usual armoury of compassion, concern, affection and attention. As it turns out, all I needed was to scare the living shit out of her. It worked too, because her outpour of emotion relieved a lot of tension for her and enabled her to find her bearings. The next day, he depression had lifted and she went back to being her.

I always resented my role as her reviver. I wondered when would it be my turn to be revived.

1 Comments:

u know, unbelievably, my dad's two sisters are called nadia and nabila!

Post a Comment

<< Home