Rated "R" for Righteous

"This Movie Is Not Yet Rated" pulls back the curtain on the secretive MPAA movie ratings board, moral "experts" determined to protect little Johnny from pubic hair and bad language.

By Stephanie Zacharek

The next time some barf-worthy line of ad copy exhorts you to see a movie through the eyes of a child, remember that in most cases, someone else already has. The Motion Picture Association of America ratings board exists to make sure that children -- they are our most precious resource, you know -- aren't unwittingly exposed to on-screen nudity, violence, drug use or inappropriate language. And if you think that sounds like censorship, both the MPAA's former head, the so-smooth-he's-slick Jack Valenti, and its current one, Dan Glickman, would race to assure you that it's not: The system is entirely voluntary; no filmmaker is required to submit his or her movie for a rating. On its Web site, the MPAA comes off as a folksy little organization dedicated to serving the greater good by helping parents "make informed decisions about what their kids watch." The MPAA ratings board doesn't want to spoil a good time, it just wants to make sure little Johnny isn't warped for life by hearing the F-word or catching a glimpse of pubic hair. And what's so bad about that?

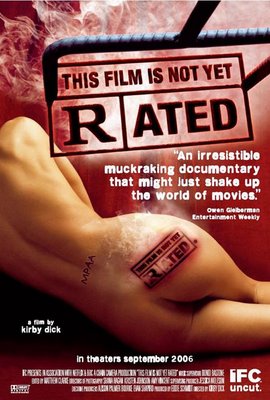

Plenty, if you're a thinking adult who cares about the vast artistic possibilities of moviemaking, both within the mainstream and outside it. That's the driving concern behind "This Film Is Not Yet Rated," filmmaker Kirby Dick's exploration of the MPAA ratings board, a mysterious and anonymous group of individuals who distract us by carrying out the seemingly harmless task of providing guidelines for parents, even as they wield a disturbing degree of control - control that's only growing and deepening - over what adults can see. As Newsweek film critic David Ansen, interviewed in the film, says of the ratings system, "It's supposed to protect children, but it's turning us all into children."

"This Film Is Not Yet Rated" is a sincere, spirited, fascinating picture that scrapes away at the purportedly benign facade of the MPAA ratings board -- a facade that has been meticulously plastered, painted and gilded over the years by former Lyndon B. Johnson aide Valenti, who headed the MPAA from 1968 until 2005 -- to uncover its insidiousness and suggest the breadth of its influence. The picture, deliciously, catches MPAA representatives in one lie after another, picking up on their backtracking and doublespeak about their motives and modes of operation. At one point Matt Stone tells of how the 1997 feature he made with Trey Parker, "Orgazmo," received an NC-17. When he approached the ratings board chairman, asking what he could do to get an R, he was told that the board couldn't give specific guidelines -- "because that would make us a censorship organization," Stone recalls her saying. Later, when he and Parker submitted "South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut," which also originally received an NC-17, Stone again asked what he could cut to get an R. That time, he received an explanation of the specific words and acts that had to go. (Stone attributes the different treatment to the fact that "South Park" was released by a major studio, Paramount.)

"This Film Is Not Yet Rated" includes interviews with a First Amendment lawyer, a box-office analyst, two former ratings board members, and numerous filmmakers who have had pictures slapped with the dread NC-17 rating, including John Waters ("A Dirty Shame"), Wayne Kramer ("The Cooler"), Jamie Babbit ("But I'm a Cheerleader"), Mary Harron ("American Psycho") and Kimberly Peirce ("Boys Don't Cry"). (Waters' movie was the only one of those that couldn't be trimmed to receive an R.) An NC-17 rating -- or, for that matter, no rating, if a filmmaker refuses to submit to the ratings board at all -- can be the kiss of death for a small picture, or even a big one, since it severely limits how a movie can be advertised. Many news outlets won't run advertising for NC-17 or unrated pictures, and most theater chains won't show them. As box-office analyst Paul Dergarabedian points out in the film, the difference between an R rating (which means children under 17 can be admitted with a parent or guardian) and an NC-17 one (which means no one under 17 can be admitted at all), can be millions, or even tens of millions, of dollars. That's a potent and direct refutation of Valenti's claim, documented in the film, that ratings make no difference at the box office.

The MPAA is a trade association -- it was founded in 1922 to advocate for the American film industry -- that serves the six major studios, and its board is made up of chairpersons and presidents of those studios. The ratings board, conceived in 1968 by Valenti, is a group of 10 to 12 individuals employed full-time by the MPAA, each of whom serves for a term of several years. The identity of these individuals is kept secret, "to protect them from influence," Valenti has said. But according to MPAA rules, they are always parents, or people who have raised children. In stock footage used in the film, Valenti intones that they're "neither gods nor fools," although they throw their weight around like the former and collectively seem to have about as much sense as the latter.

In pursuit of these mysterious creatures of darkness, Dick decided to hire his own private detective to smoke out the identities of the board, and the most entertaining and exhilarating sections of "This Film Is Not Yet Rated" are the ones showing how she painstakingly located and identified each member of the group. Her name is Becky, and she's appealingly straightforward even when being sneaky, as when she goes about collecting pictures of all but one of them, caught unawares as they go about their everyday business.

As if her ferreting out of the ratings board members weren't enough, Becky also uncovered the makeup of the MPAA appeals board, a separate group whose identities are also kept secret. The appeals board is the group a filmmaker must submit a film to if unhappy with the rating granted by the ratings board. And as Dick shows us, the appeals guys are an even more insidious bunch of operators than the ratings crew: They include a buyer for Regal Cinemas, a vice-president of sales for Sony Pictures, the CEO of Fox Searchlight, and vice-presidents from both Landmark Theaters and Loews, as well as two representatives of religious groups, one Catholic and one Episcopalian. That means if your film doesn't survive the MPAA's moms and pops, those self-appointed guardians of our moral standards, you're really in trouble, because then you have to go up against the suits and the cassocks. In other words, this is a case of big business and organized religion putting their heads together to render a moral judgment on a filmmaker's work -- a judgment that could affect how much money a movie makes, or whether it even gets released at all. That's a nightmare at worst, and at best the punch line to a very bad joke.

Dick himself is a mischievous presence, and he obviously relishes the fight he's picking here. There's a lot of information packed into "This Film Is Not Yet Rated," but Dick's cool scrappiness -- which sometimes leaks over the line into smugness -- is what really informs the picture. Dick takes impish delight in the ridiculous conversations he had with Joan Graves, the chairman of the MPAA ratings board (and the only member whose identity is made known by the MPAA to the public) and the MPAA's surly lawyer Greg Goeckner, both of whom he had to deal with in the course of submitting "This Film Is Not Yet Rated" for rating. (Dick appealed the ratings board's original NC-17, but he couldn't get the ruling overturned.) It's also great fun to hear Waters recount details from his own experience with the appeals board: They told him, as he went in, that they served cookies -- but he was not to get any crumbs on the floor.

The movie makes some smart points about why the MPAA is so fearful of sex: Harron points out that "unleashed" sex -- particularly gay sex -- is viewed as a powerful force that could rend the fabric of society. In other words, because sex is so uncontrollable, it's the very thing that must be controlled, at all costs. But even though many of the assertions made in "This Film Is Not Yet Rated" are right on the money -- and amply supported -- Dick and his interviewees often undermine their own arguments with shoddy logic and harebrained connections. One sequence features director Wayne Kramer and star Maria Bello talking about how frustrated they were that, because of its explicit sex scenes (and, specifically, a flash of Bello's pubic hair), "The Cooler" at first received an NC-17 rating. (Kramer received an R after he recut the movie.) Both Kramer and Bello speak intelligently about how important it is for movies to reflect human experience, including sexuality -- and then Kramer defensively adds that, in this particular sex scene, the characters are actually in love. So? For Kramer to justify a sex scene as masterly and sensitive as the one he, Bello and William H. Macy achieved by assessing how "in love" his characters are is exactly the kind of moral conjecture that the MPAA ratings board itself might apply.

Dick and some of his subjects also make the point -- and they're not wrong -- that violence often gets a free pass from the ratings board, while sexual content, particularly anything pertaining to gay and lesbian sex, gets the board's big white panties in a twist. But instead of leaving the observation at that, Dick allows several of his interviewees -- one of them an actual Ph.D. -- to posit that violent movies actually cause violent behavior. (When "experts" make that argument, they always proceed as if such a link has actually been proven, even though none has.) Dick is essentially saying, Movies don't control our minds -- except when they do. He also includes a rapid-fire montage of scenes depicting violence against women, designed to make us recoil. But even those snippets are taken out of context, with no regard to the filmmaking or the story around them -- exactly the kind of dumb, compartmentalized thinking that drives the MPAA ratings board.

Even more dispiriting is when Babbit speaks about when "But I'm a Cheerleader" first received an NC-17 rating, largely because of a scene in which Natasha Lyonne masturbates while fully clothed. She goes on to express her outrage that, at the time, she saw "a million times" the trailer for "American Pie," which, she claims, shows Jason Biggs masturbating with a pie. Dick illustrates with a clip showing Biggs sprawled on a kitchen counter, face-down, the splooshed pie oozing out around him. That would have been a great little touch -- except that particular pie-masturbation sequence doesn't appear in the "American Pie" trailer -- it doesn't even appear in the theatrical release of the movie. It only appears in the unrated version, available on DVD. (In the theatrical release, we see Biggs holding a pie plate to his crotch -- a little weird, but barely even suggestive.) Babbit has falsely recalled that she saw it in the trailer, and Dick either fails to catch the error, or purposely misrepresents the reality.

In a picture that sets out to puncture the hypocrisy and duplicity of the ratings board, that's a pretty significant lapse. Even "American Pie" obviously had to do its little deferential dance in front of the ratings board, a fact that might have been used to reinforce Babbit's point: What's wrong with showing teenagers masturbating, anyway? Instead, she and Dick use "American Pie," misleadingly, as an example of a bigger, more successful "them" getting preferential treatment over a smaller, struggling "us."

While it's true that independent filmmakers have a much tougher time in front of the ratings board than big-studio directors do, the reality is that the MPAA's grandiose moral pronouncements, handed down in the form of ratings, don't serve mainstream audiences any better than they do moviegoers who seek out pictures on the fringe. "This Film Is Not Yet Rated" takes on the MPAA ratings board as no other documentary has done. But it fails to ask the most important question: Why should there be a ratings board at all? Parents may claim that they need the MPAA's guidance. But is it really such a good idea to blindly accept the so-called recommendations of a group of people whose identity and motives are unknown to us? Does that qualify as good parenting, when many newspapers (and certain online magazines) contain more specific information on a film than the MPAA provides? Shouldn't it be part of a parent's job to find out for him or herself what a given movie might contain, instead of allowing a faceless organization to decide what's objectionable?

One of the arguments often made against the abolishment of the ratings system is that if we didn't have it, we might then have government censorship. But if that were the case, as First Amendment lawyer Martin Garbus points out in the film, at least movies would then be subject to judicial review, instead of the moral whims of a bunch of allegedly average parents.

The MPAA has somehow gained the trust of parents without earning it. If the MPAA had its way, we'd achieve a completely watered-down, desexualized culture, approved for a general audience. Our kids would grow up to be perfect creatures who never swore, touched anything harder than lemonade, or had anything but heteronormal sex. We could take pride in the way we protected our children; maybe we'd eventually forget how we robbed ourselves.

This article appeared on Salon.com

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home